Insights

There’s Engineering Help If You Need It

Reprinted with permission from DesignNews. Read the article on designnews.com here

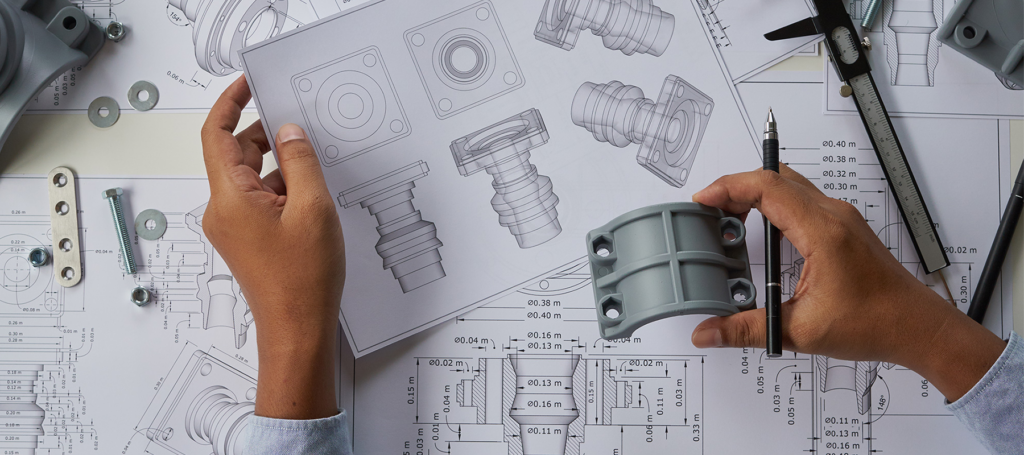

Engineers can work with outside development partners or contract manufacturers to help get projects across the finish line.

If you’re an engineering manager or project manager in product development, “a lot of times you’re stuck with a bigger plate than you can eat or a bigger bite than you can chew,” Brian Magill tells Design News. “You’ve got a number of competing priorities for how you’re going to get a product developed, tested, and productionized to launch it to the market.

“There’s a lot that goes into it, especially in a regulated industry like medical devices,” he continues. “And then if you’re working with multiple product launches or multiple development efforts at the same time, it can become a juggling match with the different resources that might be available to you at your company.”

As director of product development for Prodigy, Magill works with OEMs and their engineering teams on front-end product development of medical devices, consumer electronics, and a range of industrial equipment. Given such experience in multiple industries, the firm can share best practices from one industry to another.

Magill will be speaking in the Feb. 7 IME West panel discussion, “The Best of All Worlds—Collaboration with Internal Engineering, Contract Manufacturers, and Outside Design Firms.” He will be joined by Jenna Joestgen, director of engineering solutions–Healthcare/Life Sciences at Plexus; and Gene Payne, principal product development engineer at Johnson & Johnson Surgical Vision.

Engineering teams may be feeling these days that there’s more work to do than the available resources at their companies, “whether that’s through just firefighting or leaning down of engineering staffs or attrition or things like that,” says Magill. “We want to stress that there are capable resources out there that can be utilized, and you don’t have to necessarily hire someone for a full-time job. You can leverage the capabilities and learnings of outside development partners such as Prodigy or sometimes contract manufacturers such as Plexus.” Magill hopes that session attendees will “get a deeper understanding of what’s available to them as far as resources to help complete their projects,” he adds.

Engineers should be working with contract manufacturers and outside design firms, and engineers often help select them, Magill says. “We’re working with someone from purchasing in combination with someone who’s a technical leader or in a technical role evaluating our capabilities,” he explains. At the very least, engineers “should be aware of what’s going on, and at the end of the day, we are all on the same team. We want to get a product out to market. And we don’t want to view the engineers who work at an OEM as competition.”

Communication With Engineers Is Critical

“A lot of times we’re working hand in hand with engineers, and it’s only through good sharing of information, learnings, and expectations that we can get a good end result,” Magill says.

With medical device development, “the level of scrutiny and risk management goes up, and there’s a lot of regulation to deal with,” he says. “So, it’s in [everyone’s] best interests to keep lines of communication open to keep a clear eye on what risks are coming up. And the only way [engineers] can do that is to at least have some technical understanding of what we’re doing.”

Also, there may be several different engineers who interact with the product during its development. “If you look at it in terms of a typical product life cycle, you have phase gates that go from concept to early prototyping to alpha prototypes to beta prototypes to production. And it’s very rare that the same engineering team is going to be present with that product throughout its whole life cycle, even after launch,” he explains. “There’s post-market surveillance and product improvements and iterations and things like that.

“Then, within a product you have different systems that have different technical needs and capabilities. So, you might have an overall systems architecture that has a systems engineering group working on it. You might have a mechanical subsystem, an electronics and electrical subsystem, and a software subsystem, so you have these different teams of engineers along the technical path and along the product lifecycle path.”

Magill provided an example of working with an outside firm to integrate or develop a system such as circuit board that talks to the cloud with IoT capability. Engineers create specifications pertaining to size, power, and other features and hand them off to other engineers or an outside firm. And then there are prototyping, testing, and production activities. “Engineers have to do it well enough to hand off to somebody else to do the detailed engineering and execution and prototyping. But the company doesn’t want that engineer who’s brilliant at coming up with ideas sitting and looking at all the production launch statistics to make sure that the parts are within spec,” he says.

A Careful Balancing Act

Engineers may develop a list of requirements a mile long, and there may be competing requirements, Magill says. “We have to work in the realm of the possible, so sometimes there are tradeoffs that have to be made, and again, having lines of communication with everyone who’s working on the project [is important]. You can more quickly identify where those conflicts are and what tradeoffs need to happen and run those decisions by the appropriate decision makers.”

Tackling Challenges Together

“The tradeoffs themselves can be a challenge,” Magill says. “When you’re dealing with something new, you have competing requirements, and you have to manage what’s a priority and what’s a must-have versus a nice-to-have. Early on we try to look for what those tradeoffs are and start to gently question the stakeholders about what’s most important.

“We try to get people to think about what’s most important to the customer and can we rank or prioritize the requirements so that we can make some of those tradeoff decisions a little bit earlier and be working on the right stuff and the right performance metrics,” he says.

“The other difficult stuff is just the engineering part of it, which we’re all trained to do. We all like to design stuff that satisfies some need and get it out there. So that’s challenging in and of itself, but that’s what we signed up for.”

External factors like supply chain issues can make things difficult, too. “Especially the last few years, right? If you’ve got critical parts for a prototype, [they could] get held up in some global supply chain disruption. We had a critical component, which was sourced internationally, that ended up being delayed due to an unforeseen regional conflict,” he says. “That can make life difficult if you’re counting on something and everybody’s running lean, and something doesn’t get here, or you’ve got a year lead time on something. Market disruption or anything like that can introduce a challenge as well.”

Bringing It All Together

So, who’s responsible for looking at the whole design?

“A lot of times there will be a chief engineer or a top-level systems engineer who’s responsible for looking at the whole design [and whether] all requirements were met, but to predate that you need a good set of requirements, which is where you need a product owner or a product manager who understands the customer and their needs,” he says. “They have to be able to clearly communicate that from a customer standpoint and then a systems engineer or a lead engineer can translate that into product requirements.”

Firms like Prodigy can help, but it depends on the level of the product. “The bigger the system, the bigger the risk, the bigger the number of subsystems involved. That level of management or ownership is reserved for the OEM to put all together. Because at the end of the day, they’ve got to own it.

“But for some smaller systems or smaller pieces of equipment, we’ve done the job of putting together all the requirements and making sure that everything matches. Outside the medical industry, it’s a little more typical if we got something that a consumer products company hands us.”

Join Us at IME West to Learn More

Magill hopes that engineers will come to the session to learn about the support that’s available. “Resource constraints are real, right? And whether it’s due to the factors that I talked about, whether you have somebody who leaves, you’re always looking for more help, right?” he says. “There’s a lot of people out there who have done things with the technology that you’re looking to incorporate or who have built prototypes and been through a testing phase and successfully launched products. They’re out there to help you get more stuff done faster and to a higher quality level.”

Please join us for the Feb. 7 IME West panel discussion, “The Best of All Worlds—Collaboration with Internal Engineering, Contract Manufacturers, and Outside Design Firms,” in Room 203AB.